030: What to do when you can't get history "right."

Or, this character has to die and I can't decide how, help!

Hi friends,

I’m writing to you from a coffee shop, something I haven’t done since March 2020. I can’t tell you how thrilled I am to be able to sit on a patio and type my little stories on my little iPad, surrounded by people on dates and reading books and writing. It feels a little like coming back to life; it feels a little like coming home. I love my home office (messy as it is, at the moment) but being outside, at a coffee shop, has an energy to it that a home office just can’t achieve.

This week I’ve run through several ideas for essays to write about. I thought about the ‘starving artist’ cliché and the way the world is shifting and self-discipline and so much else but I think I’ve settled on one thing: how to make tough story choices as a writer, especially ones you personally find distasteful. So let’s hop right in.

My first encounter with historical fiction came in the form of the Dear America children’s book series. It chronicled major moments of US history through the perspective of fictional girls aged roughly 12-14. I remember So Far From Home: the Diary of Mary Driscoll, an Irish Mill Girl, Lowell, Massachusetts, 1847especially vividly. There is a moment in it when a beautiful girl’s neck is broken when her hair gets caught in a machine while she’s weaving cloth in a mill, and I’ve never forgotten the horror I felt the first time I read it. When I later learned about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, it was through Mary Driscoll’s eyes that I was imagining the fear, the pain, and the tragedy of those deaths.

This is one of the things that I love about historical fiction. When it’s done well, historical fiction has a richness to it that can seep into your memory, into our shared histories. It can make history relatable in a way that history classes often can’t or don’t.

But historical fiction is also necessarily biased. In the same Dear America series, there are a couple of books that deal with slavery. One is about a freed girl and the other about an enslaved girl. I read A Picture of Freedom: The Diary of Clotee, a Slave Girl, Belmont Plantation, Virginia 1859when I was 7 or 8, and it did not prepare me for the true horrors of American slavery. While it doesn’t whitewash it and make her seem happy to be a slave (the passage I remember most vividly is the one when she learns to spell F-R-E-E-D-O-M) it certainly sugarcoats the system for a young audience.

(A Picture of Freedom does have the benefit of being written by a Black woman, while So Far From Home was written by a white dude who certainly will never understand what it was like to be a young girl oppressed for being Irish in the 19th century.)

A lot of planning has to go into historical fiction writing. Unlike almost any other fiction genre where you have the option to find the story as you write it, in historical fiction the story is already mostly set for you. The Dear America series is enduring in part because it sets invented regular girls against real historical backdrops. The time period and population group each girl comes from is researched so that their story is a “typical” Irish immigration story (and etc), but they rarely include real historical figures. If you want to include real historical figures, heaps of research have to go into it, and your story is bound by that research.

Well, mostly.

There are famously inaccurate portrayals of historical figures. Reign comes to mind since I finally finished it a few days ago. Its portrayal of Mary, Queen of Scots is wildly inaccurate (and the finalé reads like they found out they were being canceled halfway through filming the episode; it’s a rushed and half-assed conclusion in addition to being wrong) and drew heated reviews from historians and critics alike for that. As did the movie, Mary, Queen of Scots with Margot Robbie and Saoirse Ronan. The heat comes in part because no one has done Mary’s story justice on screen, which is a shame because she led a remarkable life; any soap opera-y version of it rings hollow.

Supposedly, the reason these portrayals go off the rails is that the creators think everyone knows the story of Mary so well that they have to “keep it interesting” by adding extra drama. It’s a flawed premise though—they know what happened to Mary and Elizabeth because they’ve done the research, but the regular public doesn’t.

This is all on my mind because, in January, I began working on a historical fiction novel. In very broad strokes, it’s about a woman whose husband is murdered and the decade-long revenge spree she goes on. I started out strong with plotting and writing, but in March I ran into an interesting plot point: the woman’s oldest daughter died a few months before her husband did. Obviously, this has to impact her revenge spree, right? How do you lose your daughter and then your husband in the space of a few months and not be blinded by your grief?

But there’s a gaping hole in the historical record. See, this all happened in the 14th century, so how the daughter died and why was never recorded. I know she gave birth and then she was dead within a year. I have no idea if her husband remarried or if she had other children; I don’t know anything about her relationship with her parents, even. I just know that she lived and died.

In some ways, for a historical fiction writer, this is a gold mine. Without a clear record telling me what happened, I’m free to completely make it up.

But, for me at least, there comes an ethical dilemma with that.

Hear me out: In stories like Reign, creators must take creative license with things like conversations. There weren’t recording devices in Mary’s court, so we don’t have exact records of who said what when. We have summaries, we have diaries, we have letters, we have hearsay, but without a recording, we will never know what everyone was saying to each other. So even when plot points follow history, the conversations surrounding them are made up—they necessarily have to be.

But with Reign especially, some of those conversations got tiresome. Mary was a Catholic queen in a Protestant country. She faced people who believed queens needed a king to rule and people who believed her faith made her a bad leader, and often some combination of both. We know that happened, and it’s also not hard to believe it happened because people today still think that women need men to rule them. It isn’t new to show men hating her because she’s a woman.

It’s also not interesting anymore.

And for me, this is the problem. I’m so bored of men hating women. Get a new hobby.

This character’s death that I’m sitting with could go a few ways. It could be that she dies slowly after childbirth and her husband is heartbroken. It could be that her husband forced her to get pregnant again too soon after childbirth and that killed her. It could be that she died of some unrelated-to-childbirth illness or accident. Whatever I choose, her death is sad.

So it’s a storytelling problem but also, in my head, an ethical question. Do I go with the most likely scenario, which is the second option—her husband forced her to return to “marital duties” too soon, and her body couldn’t take a second pregnancy? Or is it okay to be so tired of misogyny in fiction that I choose a nicer ending for her? One that doesn’t remind people over and over again that women were property for centuries. Yes, it’s true, but does that mean we have to reckon with it every day?

If I choose the nicer option, am I sugarcoating history, even just a little bit, like A Picture of Freedom did?

Should I choose to stomach a more violent end for this young girl because it also gives her mother more anger in the story, fueling her desire for revenge?

There’s no easy answer. In the end, the choice doesn’t completely dictate what happens in the rest of the book—history does (and the story is a doozy). But it does matter for the main character’s motivation. Is she angry at all men or just the man that murdered her husband? Is she aware of how unfair it is to be a woman in the 14th century, or does she use that feminine energy as her source of power? Is her mission political or personal, or a very dangerous combination of both?

Currently Reading

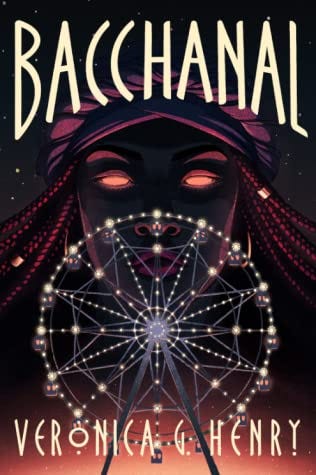

To be honest, I haven’t been reading as much lately, and I only started reading Bacchanal today so I don’t have much to say about it yet. I’m intrigued by the premise though:

Abandoned by her family, alone on the wrong side of the color line with little to call her own, Eliza Meeks is coming to terms with what she does have. It’s a gift for communicating with animals. To some, she’s a magical tender. To others, a she-devil. To a talent prospector, she’s a crowd-drawing oddity. And the Bacchanal Carnival is Eliza’s ticket out of the swamp trap of Baton Rouge.

Among fortune-tellers, carnies, barkers, and folks even stranger than herself, Eliza finds a new home. But the Bacchanal is no ordinary carnival. An ancient demon has a home there too. She hides behind an iridescent disguise. She feeds on innocent souls. And she’s met her match in Eliza, who’s only beginning to understand the purpose of her own burgeoning powers.

I can say that the writing grabbed me as soon as I started reading. I think I know where the book is going, but I can tell it’s going to be quite a ride on the way there. This is Veronica Henry’s first novel, and I’m so excited to see where her career takes her.

P.S. I got Bacchanal early as part of the Kindle First Reads program, which I recommend to anyone who reads a lot and finds they can’t afford their habit. (And also likes the somewhat pointless feeling of reading a book a few weeks before it is officially published and released.) You pick one free book a month and get a discount on the others. There’s probably something ethically wrong with this (do the authors get paid? I couldn’t find an answer) but in the absence of direct criticism, I’ll cross my fingers that they do.

As always, thank you for reading. If you want to respond just hit reply. Especially if you feel like you might have strong opinions about what happens to the character I mentioned in the above essay! I really could use the help? Your message will get to me (and only me). If you liked this and think your friends might too:

Have you read last week’s article from Dr. Anna Maria Barry? It’s a fascinating look at how tea was used in Victorian Gothic fiction.

You can upgrade to a paid version of this essay collection and gain full access to the archive, as well as upcoming exclusive posts. That includes a new featured column I’m going to introduce later this month (once I figure out a name for it)! The annual subscription is 25% off until May 16, 2021.

If you received this email from a friend and you liked it, you can subscribe to the free twice-monthly series right here:

All the best, friends!

Valorie