029: Black Tea: Tea and the Gothic

Hi friends,

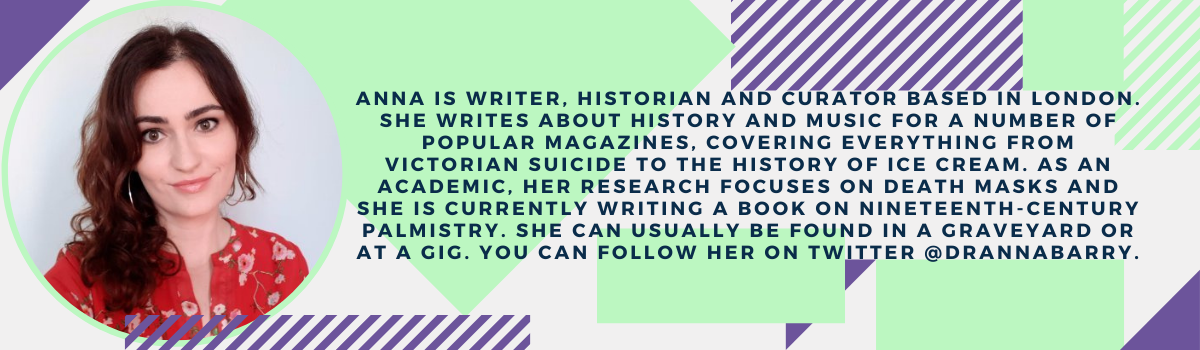

As promised, it’s time for the first-ever Collected Rejections guest author essay! I’m so excited to host historian Dr. Anna Maria Barry writing about the Victorians being weird about tea (and writing about it). As you all know, the Victorians are close to my heart, so I’m always excited to learn about a new weird thing from them, and Anna studies a really interesting subsection of their culture.

This month’s guest author essay (a section I really ought to name) is going to be free forever so you can get a feel for the types of essays I’ll be publishing here in the future. Starting next month, it’ll be behind a paywall—and I’m very excited for you to see what we have coming next month! Keywords: Interwar, mourning, ghosts. You can get 25% a yearly subscription until May 16.

Have an idea you’d like to publish in Collected Rejections? Awesome! Pitch us here:

Black Tea: Tea and the Gothic

by: Anna Maria Barry

We had a kettle; we let it leak:

Our not repairing made it worse.

We haven’t had any tea for a week…

The bottom is out of the Universe.Rudyard Kipling

Here in London, tea is the answer to almost everything. Have you had some bad news? Or is there something to celebrate? Are you feeling tired, or a little unwell? Have visitors arrived? Do you have a hangover? Better put the kettle on…

Around the world, Brits are known for their love of tea and the rituals that surround it. You can still spark a boiling debate, here, with questions like, ‘should the milk go in first or last?’ (always last) and ‘which tea is the best?’ (it’s loose-leaf Assam for me). A friend and I once spent the day at a literary festival where we decided to join a tea-tasting session that sounded fun. When we made the error of mentioning that we occasionally use teabags rather than loose-leaf, the people sharing our table recoiled in horror. We became pariahs.

Tea at a book festival is no random pairing. A mania for tea is part of our cultural identity that has saturated British literature. Whole books and theses have been written on tea in the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, for example, and literary tourists can enjoy a Mad Hatter-themed afternoon tea at a fancy London hotel.

What is less appreciated is how tea has seeped into the darker side of literature, infusing many of the best-known works of gothic fiction written in the British Isles. As a marker of civilised society and symbol of safe familiarity, tea is a tonic for the haunted – but it is also ripe for subversion.

In Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for instance, the vampire’s bug-eating disciple Renfield has a novel use for his tea things. This asylum inmate ‘has the sugar of his tea spread out on the window-sill and is reaping quite a harvest of flies.’ He refrains from eating his tiny victims, using them instead to lure a more satisfying spider.

Tea also appears in Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. When Utterson and Poole break into Jekyll’s cabinet they find the ‘contorted’ body of Hyde, who has poisoned himself. The men search in vain for Jekyll, as they don’t yet realise that the novel’s eponymous duo are in fact the same person.

Lying next to Hyde’s ‘still twitching’ body is a tea tray:

the tea things stood ready to the sitter’s elbow, the very sugar in the cup. There were several books on a shelf; one lay beside the tea things open, and Utterson was amazed to find it a copy of a pious work, for which Jekyll had several times expressed a great esteem, annotated, in his own hand with startling blasphemies.

The comfort and order of the tea tray is juxtaposed with the twitching corpse, the suicide, the poison bottle, the blasphemy. It is the normalcy of tea which throws these horrors into relief – they are taking place here, in the safe world of afternoon tea, not in some faraway Transylvania.

Daphne du Maurier, one of my favourite authors, was steeped in the gothic tradition. Her masterpiece Rebecca is studded by teatime scenes. In fact, so frequent are these caffeine breaks that they were parodied by much-missed website The Toast. This post skewers the nameless narrator torturing herself over endless cups of too-hot tea, nervously crumbling her cake as she agonises over the omnipotent spectre of her husband’s first wife, Rebecca.

The ‘solemn ritual’ of sumptuous afternoon tea should be a comfort, but instead, it unsettles the second Mrs de Winter, highlighting her feelings of inadequacy. She imagines the glamorous Rebecca indulging in buttered crumpets, sat in the very same place: ‘Did she too have tea under the chestnut tree?’ The tradition haunts.

While tea makes a cameo in all of these dark tales, there is one story in which it takes a starring role. ‘Green Tea’ by Irish purveyor of ghost stories, Sheridan Le Fanu, was first published in 1872 as part of a collection called In a Glass Darkly. The collection concerns the adventures of Dr. Hesselius--a sort of occult Sherlock Holmes (and proto-Van Helsing)--who investigates the connections between strange happenings and the unconscious.

(Though ‘Green Tea’ is often anthologised, it is perhaps not as well-known as another short story from the same collection: ‘Carmilla’, a much-adapted story about a lesbian vampire which pre-dated Dracula by 26 years and undoubtedly inspired Bram Stoker.)

‘Green Tea’ centres around the case of a clergyman called Jennings who is tormented by a demonic monkey with glowing red eyes. He describes how, even in ‘total dark,’ this monkey is ‘visible distinctly in a halo that resembles the glow of red embers.’ Jennings continues: ‘It grows at first uneasy, and then furious, and then advances towards me, grinning and shaking its paws’.

This monkey haunts the Reverend’s every move, becoming increasingly malevolent. It squats on his Bible when he’s trying to preach and eventually urges him to commit suicide. The tortured Jennings cuts his own throat with a razor and bleeds to death before Hesselius can help him.

Of course, the all-knowing Hesselius has already figured out the cause of Jennings’ disturbing visions: He has over-indulged in green tea. Indeed, Jennings tells the doctor that he drank this concoction to excess while writing an esoteric book about pagan religion:

I used to sit up very late, and it became a habit with me to sip my tea – green tea – every now and then as my work proceeded. I had a little kettle on my table, that swung over a lamp, and made tea two or three times between eleven o’clock and two or three in the morning, my hours of going to bed.

In her essay on this strange simian tale, Melissa Dickson notes that, in early nineteenth-century Britain, there was a widely recognised connection between scholarly pursuits and the (over)consumption of green tea; a ‘marked association between the student and the teapot.’ Green tea was the drink of choice for the studious. It acted as a stimulant which fuelled literary endeavour, but it also dangerously over-excited the nerves. Medical texts of the time, says Dickson, cautioned against over-indulgence in green tea, warning that it could lead to nervous exhaustion, poor digestion, or even hysteria.

While warnings about the potential dangers of green tea go some way towards contextualising the weird visions experienced by the scholarly Reverend Jennings, they do not tell the whole story. Indeed, there was another reason for Victorians to fear green tea in particular: Much discussed at this time was ‘adulteration,’ the process by which some unscrupulous traders cut pure green tea with other (cheaper) substances. At best these included the leaves of other plants, but at worst they might include iron filings or even sheep’s dung. Many feared being poisoned by these illegal concoctions, and only drank green tea if they could be certain of its quality.

These fears also had a racial element. There was a distrust of the East and the Chinese in particular. Many of the warnings and pamphlets that were printed about the perils of green tea adopted the heavy use of racist stereotypes. More broadly, there was a creeping unease that tea – becoming, at the time, a staple of the British home – had its origins in the ‘untamed east.’ As Dickson puts it: ‘There is something foreign and vaguely malevolent about this substance, which has not yet been fully understood and taken under British control.’ Many critics see these racialised fears reflected in ‘Green Tea,’ embodied by the demonic monkey as a symbol of the East.

In ‘Green Tea’ then, we perhaps approach the true horror that surrounds tea: not demonic monkeys or frayed nerves, but colonial exploitation and human misery. The British taste for tea – and sweet tea specifically – was a driving force of the slave trade, as well as being responsible for systems of indentured labour on tea plantations.

It also underpinned the Opium Wars in the early nineteenth century. The British illegally sold huge quantities of the drug to the Chinese markets in order to support the tea trade. Though the Chinese tried to stop this damaging practice, they were ultimately defeated. By 1906, it is estimated that 27% of the adult male population of China was addicted to opium.

As we increasingly reckon with our colonial history in the UK, where the Black Lives Matter movement is reverberating and institutions increasingly acknowledge their culpabilities, we might read the teatime traditions of Austen, Dickens, and the Mad Hatter through a different – darker – lens.

As always, thank you for reading. If you want to respond just hit reply. Your message will get to me (and only me). If you liked this and think your friends might too:

If you received this email from a friend and you liked it, you can subscribe to the free twice-monthly written series right here:

All the best, friends!

Valorie