Hey everyone,

How is your summer going? We’re creeping up on August, which is usually when I take a month off to reset, but this year I don’t feel like I need it. Maybe it’s because I accidentally took two weeks off at the beginning of July when I had a little health crisis, but I’m feeling okay this year—rested and good, even. So even though season two of the Unruly Figures podcast will be coming to an end on August 1, I’m planning to still be writing here as normal through August.

I don’t have much else in the way of updates, but I *do* want to resurface a post I wrote last summer about working in the heat. The gist of it, if you don’t want to read the whole thing, is that—well—the human brain didn’t evolve to work in this godforsaken heat. So if you’re feeling less productive than usual and you’re tired all the time and everything seems 5% (or 10% or 25%) harder, that’s because it is! It literally is, and science says so. So cut yourself some slack.

054: Do We Ask For Too Much During Summer?

Hi friends, How’s everyone holding up in this heat? I, for one, have practically become nocturnal to avoid the worst of it. I sleep most days from about 3 pm to 7 pm, eat some combination of breakfast and dinner food that we don’t have a nickname for yet, then start up my work again. I realize this is not a possible solution for most people, but if you h…

(I have been back on my nocturnal bullshit this summer, maybe that’s also what’s helping me feel good now.)

All right, a craft essay. Let’s do this.

Let’s Talk Psychology

I have kind of a weird essay for y’all today. I loved writing the hero series, and I considered immediately jumping into other story archetypes next. They’re so fun to talk about, at least to me!

But I’ve been working on my novel again lately (got pretty distracted from it in April/May, but I’m back on my bullshit) and it’s got me thinking a lot about character motivation. I feel like most people only talk about a story plot as a series of events that have to build on one another: An event happens, someone learns x, and that forces them to do y. But sometimes the plot could veer off in different directions due to a character’s internal motivations! And that can get tricky. If a character starts making decisions to serve the plot, but those decisions aren’t based on the character’s needs, then it can seem strange or even unbelievable to readers.

A long time ago, to really check if my character’s motivations feel realistic and believable, I started checking their behavior against psychology. I love psychology anyway, so this wasn’t a big leap for me, but I think more writers should be turning to some of the psychological tools that have stood the test of time. Consider this me encouraging you to go read more articles about psychology!

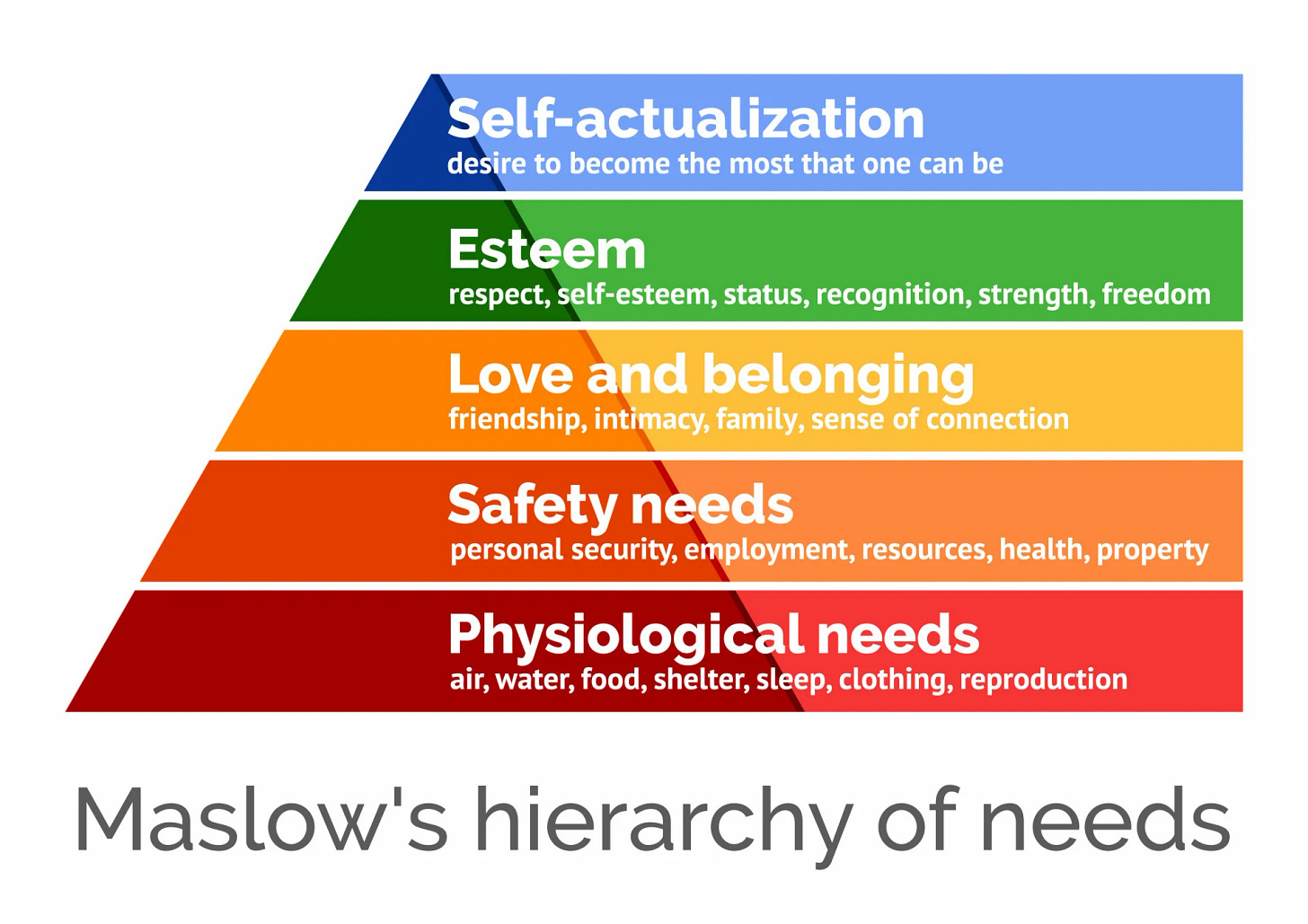

A great place to start is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. If you’re unfamiliar with Abraham Maslow, he was a pioneering mind of the humanist and self-actualization school of psychotherapy; he argued that integration of the self is the most important goal of psychological treatment. He believed that we are all individuals who need to be treated that way by therapists, instead of being lumped into diagnostic categories the way we would diagnose and treat someone with a viral infection.

But Maslow still believed that all humans needed to meet the same emotional needs to feel fulfilled. How people meet those needs and how they react to unmet needs can vary, but as a framework, he established five categories of needs that are built upon one another, like a pyramid. He believed that people could climb the pyramid, so to speak, only as they met all their needs in each lower layer.

So the basis of the pyramid is Physiological, your basic survival needs: Food, shelter, water. Above that is Safety, like good health, a job, feeling physically safe and secure. Above that comes Love and Belonging—it’s all about healthy relationships and feeling connected to people. The fourth is all your Esteem needs, like freedom, self-confidence, and respect. And the fifth, the pinnacle of the pyramid, is Self-Actualization—basically, reaching one’s full potential and feeling existentially satisfied. Maslow called these five layers the hierarchy of needs. Again, he believed that humans couldn’t achieve things from an upper layer without first meeting all the needs of the layer(s) beneath it. I think this is flawed (plenty of loving families starve together, to be blunt) but the hierarchy is still really useful.

On a large scale, the hierarchy of needs sets out what drives human behavior. It can be used to explain why communities throughout history have battled over water or arable land—their need to have food and water outweighed their need for safety and security, so violent conflict becomes worth it. People can’t achieve peace if their children are starving. They need to fulfill that bottom layer first.

Because it explains human behavior, Maslow’s hierarchy can be adapted to writing fiction. It’s especially easy for stories that follow the classic hero’s journey, but it also works for stories that don’t.

Where Does Your Character Start On the Hierarchy of Needs?

Where your character is starting on Maslow’s pyramid is where you want to begin examining how their needs inform your plot. And that spot is going to vary. For instance, in a coming-of-age tale, you might be looking at a kid who has all their Physiological and Safety needs met—they have food, a home, they go to school, all that. So their character arc throughout the story is going to start them at the middle Love and Belonging stage—maybe they have a good family but they don’t have friends at school, so they need to meet that need to move up the pyramid. This kind of story can end at the Esteem stage, where they figure out they’re good at music and they get accepted by a group of friends. It can also end at Self-Actualization, where they gain their friends, go on to win the rap battle (or whatever), and figure out who they are as a person. It just depends on what you want to write.

But maybe your character is starting lower on the pyramid. Maybe your character is broke and doesn’t know how they’re going to afford dinner. That’s a very different story, everything then is about meeting their Physiological needs. Whether that means stealing food or selling a prized possession, they have to do whatever it takes to eat. So your plot is going to focus on that.

Or, your character might start on a higher level and then fall down before climbing back up. This is every single horror arc. Things are okay, maybe even good, and then something goes horribly wrong and the characters slide all the way down to Physiological needs. Frankly, no one cares if they have status in their community if they might not survive the night! (And, in horror, the people who do prioritize status over life usually die.) The story then usually ends with the protagonists somewhere on the Safety or Love and Belonging layers. Maybe they need to rebuild their home, but hey, at least the monster is dead and they’re safe.

Ascending the pyramid is not a straightforward journey. Characters can bounce around, climbing up and sliding down. Sometimes characters don’t know where they are on the pyramid! A lot of romance stories will see characters striving to meet their Love and Belonging needs, only to realize that a Safety need is standing in their way. Maybe they’re single because their job is too demanding or because they don’t feel psychologically safe after a traumatic event. They have to figure that out before they can have their happily ever after, so the plot sees them backtrack to the lower level.

Using the Pyramid to Create Obstacles

The middle bit of a story is often the hardest, right? Your character can’t just set a goal and sail on to it, they have to struggle! They have to fail and try again, fall down and get back up. Otherwise, the story is boring!

Thankfully, Maslow’s pyramid is useful for this too. Say your character is a child living on the streets and trying to find their family. Their ultimate goal then is on the Love and Belonging tier, but access to food and other resources stands in their way. They can’t just walk into the library, Google their mom’s name, and voila! Family!

So, maybe they have regular access to food and shelter, but they need clean clothes to get into the library. Or maybe their Physiological needs are met, but they’re trying to avoid some kind of terrible system that disappears children (I’m thinking Hunger Games, but worse), so they need to somehow fly under the radar to stay safe. So your plot will be informed by how they stay safe on the journey to finding their parents.

Harry Potter is a good example of part of a tier acting as an obstacle. Throughout the series, he is reaching for Self-Actualization by fulfilling the prophecy of his birth, but he gets stuck on the “Voldemort killed my parents!” complaint for a long time. He’s traumatized by their murder and his subsequent abusive upbringing, and that leaves him realistically trapped at the Love and Belonging level. All his lower-stage needs are met; he has friends and an adoring public for most of the series, but the family piece is missing. Even as he starts to gain the respect of his peers through Quidditch, how much he wishes his father could see him play comes up again and again as a reminder that this family piece is missing. This doesn’t change the arc of the series, but it does impact his emotional arc and drives smaller plot points like arguments with Ron and Hermione. It’s not until he accepts his found family and his place in the larger community of the Wizarding World that he can focus on Esteem and Self-Actualization. Arguably, this isn’t complete until he summons his parents’ ghosts right before his 7th book battle with Voldemort in the woods.

Like Harry’s family trauma, you can harness missing features at each layer to create challenges to throw your character’s way. You just have to decide how they’re going to react to them based on what they’ve already achieved. And those challenges will feel more natural or believable because they’re grouped on the same psychological level. It will make sense for that character in that world. A character’s choices can start to feel unbelievable when you try to have characters reaching for the respect of their peers when they have empty bellies.

But, that introduces the major caveat when using this to write fiction: Your character doesn’t have to follow the pyramid perfectly.

Readers Value Some Things More Than Food

In real life, no one is going to say that a person should forgo food in order to gain their boss’s respect. Fill your belly first!

But in fiction, we get into this weird world of heroic behavior where suddenly these kinds of sacrifices gain near-mystical meaningfulness. For example, if you’ve seen Oppenheimer, you know that David Krumoltz’s character Isidor Rabi repeatedly offers Oppenheimer food throughout the movie. This is based on a real character trait of J. Robert Oppenheimer: The man was incredibly slender and tended to forget to eat, especially during grad school and the nuclear bomb testing at Los Alamos; his peers said that he seemed to feed on ideas instead. In real life it’s described as a bit of a character flaw; people worried about him, he was described as dangerously thin during World War II. But in the movie it seems like this amusing sign that Oppenhimer is destined for greatness: He’s so busy trying to achieve Self-Actualization (creating the atomic bomb, yikes) that he forgets those lower-level needs like eating. They’re literally beneath him.

This fiction logic is why we can have perfectly successful fictional stories about a woman saving other women and rebelling against an unjust government even though her access to potable water is not guaranteed (Mad Max: Fury Road). There are some things that readers value more in fiction, like justice and freedom. Since Furiosa has the emotional strength to escape and take the enslaved women with her, no one is going to enjoy a version of the story where she lives under Immortan Joe’s rule just because he doles out clean water. Their entire world might be trying to meet their basic Physiological needs, but Furiosa is operating on the stages of Safety and Love because those are more important to her soul or spirit.

The soul is often more important than the body in fiction, so having a character forgo scoring a goal because their ankle hurts a little is rarely going to play well on screen or on the page, even if that’s what you’d tell them to do in real life. When it’s a character as strong as Furiosa, drinking water is not enough to keep her in place when hope and freedom lie just beyond Immortan Joe’s rule.

Hope, love, integrity, justice—these are not Physiological needs according to Maslow. We can subsist without them. But in fiction, they operate like Physiological needs. Heroic characters often sacrifice food, water, et cetera for Love, Esteem, or Self-Actualization, and we love it. Those are the stories we keep coming back to. In almost every story that follows the Hero’s Journey, the protagonist sacrifices a lower-tier need in favor of a higher-tier one (and I’m saying ‘almost’ to hedge; I would bet that it’s in every single Hero’s Journey story).

That said, Maslow might point out that in my earlier example, Furiosa is not reaching for self-actualization, she’s still on the bottom and middle tiers of the pyramid. Even with fiction logic, it can be hard to have someone reach that high when their circumstances have brought them so low. Furiosa is reaching for Safety and giving up water for it. Oppenheimer forgetting to eat in favor of Self-Actualization only works because he has easy access to food; it wouldn’t work if the cupboards were bare and his family was going hungry.

Fiction logic makes skipping needs on the pyramid acceptable, but there are limits to how many needs a character can skip over or ignore before we start looking at them with concern. For instance, there’s a scene in Oppenheimer when he asks his friend to just take the oldest Oppenheimer child for a while. The kid is a toddler at the time, and his wife, Kitty, is really struggling with alcoholism, so to some extent, it’s for the safety of the child. But Oppenheimer admits that they are bad people for asking someone else to care for their child for an extended period; especially because we don’t see him making any sacrifices to take care of Kitty or their child. He’s sacrificing family, in the Love and Belonging tier, for his own Self-Actualization. It’s very selfish, and it’s one of the ways that Christopher Nolan makes him an anti-hero.

As a rule of thumb, we can take it when characters hurt themselves in pursuit of their goals. We don’t like it as much when they hurt other people in pursuit of their goals, especially when those other people are children. The Love and Belonging tier is a particularly hard one to see a character betray or ignore, and any trauma in that tier is often an origin story, for villains and for heroes.

If you’re going to have a character sacrifice a lower-tier need for a higher-tier need, the motivation has to be good. Luckily, with fiction logic, there are many ways to establish that motivation. It can be internal, like Furiosa’s desire for freedom over tyranny.* It can also be simpler—a parent skipping a meal (Physiological) so that their child can eat (Love); that happens in real life and in fiction.

There also usually needs to be a good device to make this level jump work. Aladdin is a great example of this: Our hero is catapulted from stealing food to eat (Physiological need) all the way to a challenge that straddles both Love and Esteem—he falls in love with Princess Jasmine and needs to convince the sultan that he belongs and deserves respect. How does he achieve this? The genie. Without Genie, all of that is impossible because Aladdin alone can’t meet his basic Physiological needs. Though his personality is what wins over the Sultan and the Princess, he wouldn’t have the time or resources to focus on doing that without Genie’s help. Genie acts as the device to make skipping Maslow’s lower levels possible.

Finally, How to Make It Work

Here’s a quick guide to actually using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to figure out a character’s motivations and help plot a story:

Establish where your character is starting on the pyramid.

Figure out which tier they’re trying to reach.

Check off which needs have already been met, and circle which needs are standing in their way to the next level.

Figure out why some needs remain unmet (this can be one sentence—Harry’s missing a family because his parents were murdered). This is what serves are the foundation for all the character’s motivations and reactions when they come up against these missing needs.

Brainstorm ways to have the character either meet or fail to meet those needs.

If you’re going to skip needs (or entire tiers, like Aladdin), come up with a device or extreme motivation that enables that.

Decide which needs the protagonist can sacrifice to meet their higher need (if any).

Accept that your character might slide down and climb back up as they come up against new obstacles. (In fact, the more this happens, the more people get invested in the story.)

It’s not the easiest tool in the world, I’ll give you that. But digging into your character’s psychological needs will help you figure out where they’re going to get into conflicts, what’s going to make them feel safe, and how they’re going to choose to act in any situation. And that is what’s going to make your plot feel believable and relatable.

*Before you say that this is what every revolution is about, I’ll point out that Furiosa lives in a post-apocalyptic wasteland without clean water one more time. While revolutions are often influenced by scarce resources, it is usually because those resources exist but they’re being denied to the people who need them.

I hope you enjoyed this longer-than-usual post. I know it’s a little strange, but I genuinely love using psychological tools to figure out characters and their challenges. If this works for you too, I’d love to hear it!

Last week, I released a podcast episode about Sarah Bernhardt. I get the feeling that if you liked this essay, you might also like her story. Her whole story sees her achieving Self-Actualization, occasionally at the expense of financial security or the respect of her community. Proof that Maslow’s hierarchy isn’t bulletproof.

I am only able to dig deep into these sorts of tools because many incredible people like you support Collected Rejections. If $5 a month isn’t a huge ask for you, I encourage you to become a paying subscriber! You’ll get extra writing prompts, access to our subscriber-only virtual writing sessions, voiceovers for posts, and more.

Last week I published a longer thinkpiece about Barbie, Oppenheimer, and their shared exploration of existential dread. Check it out if you’re into that kind of thing.

Hope you’re all well. Stay safe out there.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Collected Rejections to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.