036: Lichtenstein’s Terrifying, Untouchable Women

Hi friends,

When I last wrote, I mentioned that I had hired Sarah von Bargen to help me restructure my digital business and online life. It’s funny—a couple of weeks before I had talked about how clarifying applying for graduate school was for me, and this ended up being a similar experience. I had already been kicking around the idea of working with Sarah when I wrote that, but I didn’t know that the way she asked questions and encouraged me to think about myself and my writing would set the same kind of purifying fire that helped me before. I’m not ready to reveal everything that comes next—I’m still figuring stuff out!—but I am ready to say that the experience was (and continues to be) very helpful. If you’ve ever considered hiring a business coach, hire Sarah!

Now, today is US Independence Day. I used to love this holiday—it always meant a week with my grandparents, and a day of fireworks, barbecue, and fun with my cousins. This year, I don’t know, I have a hard time rooting for the US. Honestly, I’ve been having a hard time doing so since 2016. It’s just hard for me to root for a country that stands by as police kill nearly 500 citizens this year, that mocked each other as 605,000 citizens died from a fairly avoidable illness, that incarcerates thousands of it’s citizens on petty drug charges while it celebrates other thousands of citizens for doing the same drugs… But, I get the allure of celebrating today. I’m not judging the people who are celebrating, because I get it. But if you’re on your way to watch some fireworks tonight, I hope you listen to 1619 on the drive over.

Okay, let’s crack into today’s essay, which I promise is neither about America nor about business.

There are a couple of paintings by Roy Lichtenstein that keep me up at night.

He was a Pop Artist at the same time as Andy Warhol, elevating media practices like cartoons and mass-market printing techniques to the realm of high art while Warhol was looking at consumer products and the stalking of celebrity. Lichtenstein asked a lot of interesting questions with his art, like if he reproduced someone else’s art (say Tony Abruzzo’s cover of Secret Hearts no. 83) in a mass-media painting technique like, say, Drowning Girl, 1963, was it now Lichtenstein’s, or was it still Abruzzo’s?

Images from Wikipedia.

Lichtenstein borrowed a lot from other artists and, fairly or not, sometimes that’s what he’s most remembered for. But he also had these series of women who he came back to in his art practice that spanned decades. They were usually Barbie-esque versions of women: perfectly coiffed blonde hair with round eyes and unblemished skin. But they weren’t beautiful, exactly. Sometimes their fingers subtly sharpened into claws at the end. Their skin, rendered too perfect due to the lack of detail in mass-printing techniques, often looked plastic.

The ones I find strangest, who keep me up at night, are the ones he painted later in his career. They have perfect hair and wear pearls around their neck. Like many of the people in his paintings, speech bubbles hover above them, but they’re half-cropped out, rendering the women unintelligible. And they are naked.

They’re not nudes, not to me, not in the traditional sense of the nude. Lichtenstein’s women are no Lady Godiva, riding naked through the streets of Coventry to save her people. There’s no emotion, no sensuality, no sense of feeling. They’re unselfconscious in their nudity, which I guess is good, but then so was Olympia as rendered by Manet, and Venus as painted by Velasquez. Lichtenstein’s women are so removed from this tradition as to not even really register as nude at first. Their skin is blue.

Images from The Broad and Widewalls.

Not Avatar-blue but death-blue. Corpse-blue. Lichtenstein’s women, with their unsettlingly flawless skin and perfect hair, seem to me to be corpses, albeit corpses walking around trying to communicate with their voyeurs.

Wondering why he did this kept me up at night for a long time. When I was a researcher in a curatorial department, I had to do a deep dive on some of these works to better explain them for visitors. It seemed like everyone who ever commented on Lichtenstein had something to say about his women, but commentators didn’t seem to reach a consensus. These were nudes for the Pop Art era, for the 21st century! Or, these are a sign of the misogyny of the art world, these naked girls unable to communicate with us! Lichtenstein hated women! Or, as his wife would repeat, Lichtenstein adored women.

It wasn’t until I started reading Venus in Exile, by Wendy Steiner, that I started to realize that maybe something else was happening with Lichtenstein’s women. Steiner, a cultural critic and expert in the intersection of modern literature and visual art, proposes that the modernists, starting in the late-nineteenth century, started to reject the ideal of beauty and especially the ideal of Woman As Beauty. They stood in a long line of people, including philosophers and authors, who were working desperately to untangle ethics from aesthetics. The result was a rejection of beauty in art almost entirely.

One of my notes in the margins of her book (yes, I write in books, I’m not sorry) is simply, “Fridging.” Steiner talked about how one of the reasons beauty was rejected was because beauty, especially a beautiful woman, was seen as threatening because women used their beauty in a utilitarian fashion, namely to ensure their own survival by landing marriages and therefore incomes and security. From this cynicism, they started to think that beauty and beautiful women were in need of being controlled. Starting in the nineteenth century, a fictional woman’s beauty was her downfall, thereby unlinking aesthetics from ethics by making beautiful women somehow immoral because of their beauty. Early twentieth-century modernists were open in their misogyny while going about this, leaving their beautiful women to be useless fools or die tragically.

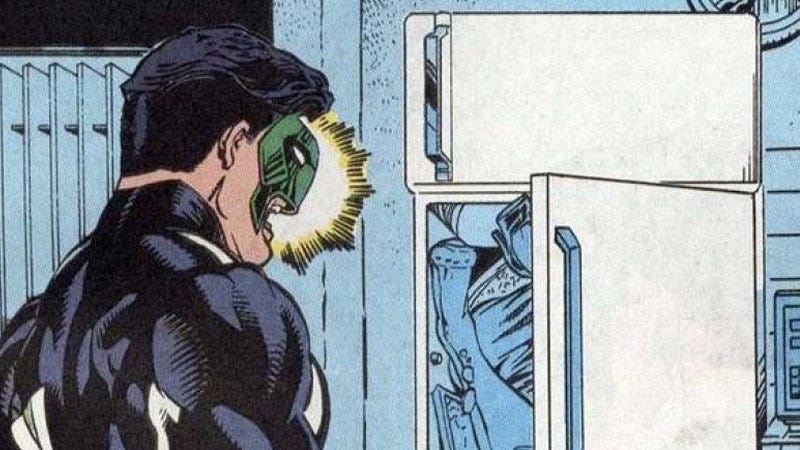

It reminded me forcefully of the practice of “fridging” a (usually female) character. The term comes from a Green Lantern comic when our hero comes home to find that his beautiful girlfriend has been murdered and stuffed in a refrigerator. Green Lantern rises to the occasion, eking out revenge in a way that brings heroism to new heights, but what does Alexandra care? She’s dead. She died to give him something to do. And, importantly, at least to me, but a lot of people don’t take it this far: Alexandra had to die because her ongoing existence would have kept Greenie at home, not being the hero he was destined to be. His attraction to her and her beauty means he is distracted from the work he has to do defeating his nemesis. If she lives, evil will triumph, basically. Her beauty is therefore linked to crime and immorality; her death to triumph and The Greater Good.

Image from Know Your Meme. Notice how even the explanation of the meme doesn’t include Alexandra? Her death, quite literally (we ARE talking about illustration), completely erases her.

Unsurprisingly, this storyline was written by a guy. Much like most of the modernist literature decrying beautiful women was written by men, just like how much of this whole discussion of rejecting Woman as Beauty was led by men (though, it should be said, Mary Wollstonecraft contributed to all of this too). While there’s a lot to be said for the value of unlinking Good from Beautiful and Bad from Ugly, I can’t ignore that the real victim of this discussion was women.

Because it seems like they couldn’t quite do it. Maybe I’m cynical or maybe I’ve just read too much psych 101 material, but to me this all just reads like the classic childhood move of hating the person/group/institution that rejected you. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em, but if you can’t join ‘em, hate ‘em. For a century, men tried to philosophize their way out of the appreciation of beauty, and of their own distraction caused by their attraction to beautiful women. When they couldn’t do it, when they couldn’t successfully divorce Beauty from Woman and Good, they just rejected all of it. Instead of beautiful female characters capable of evil, of ugly women who do brilliant things, of painting average-looking women, all these men just threw in the towel. They stopped painting women, they stopped seeking out beauty.

Lichtenstein, painting his women in the mid and late twentieth century, inherited this mentality, this rejection of beauty and beautiful women. A lot of his canvases simply depict empty furnished rooms, ones which were probably decorated by a woman who has since been evicted. Many of his women are made up of composite parts, beautiful in the Hellenistic way of having “perfect” proportions, but terrifying in their undead appearance. Much like Alexandra and all the other female characters who have been fridged, Lichtenstein’s women exist in a liminal space where they move the story along but they can’t communicate with us.

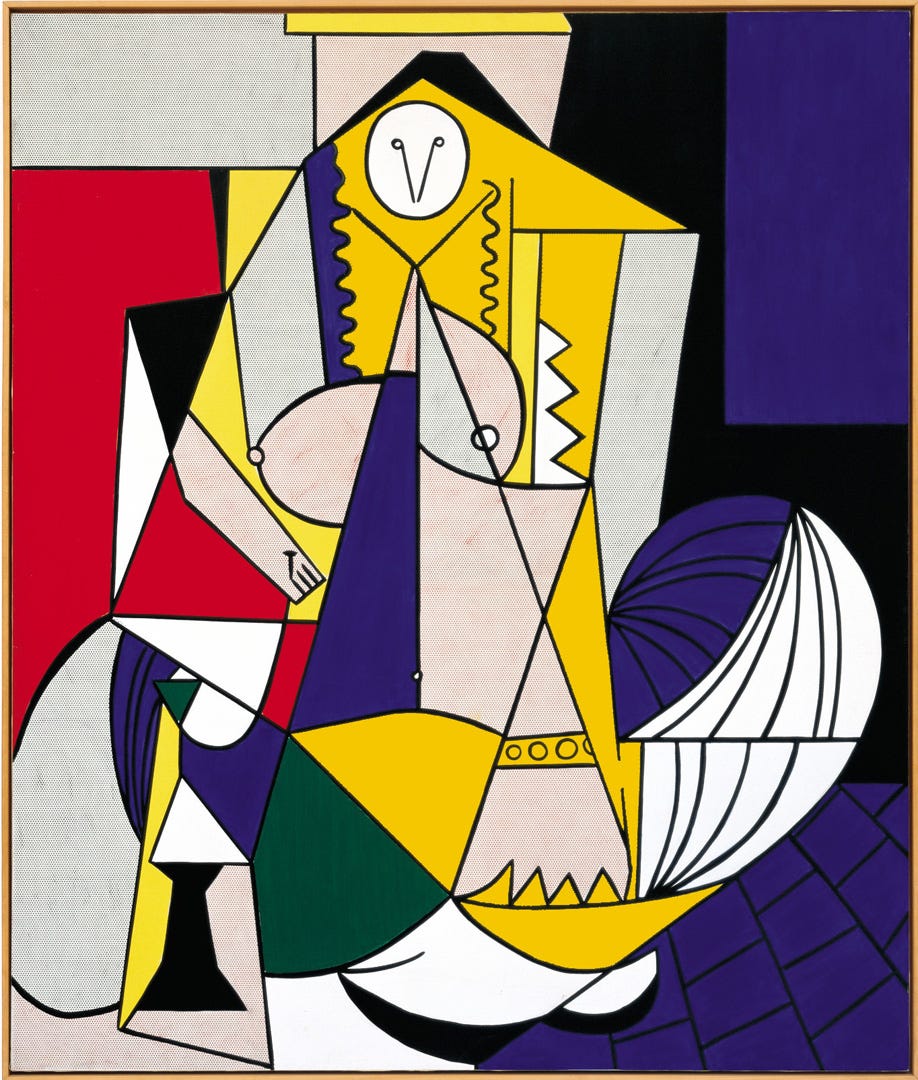

One, in particular, is monstrous in a captivating way: Femme d’Alger. It’s one of Lichtenstein’s borrows—he’s borrowed from Piccaso’s Les Femmes d’Alger, which is, in turn, a tribute to Eugène Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement. In Delacroix’s original two paintings by the same name, one painted in 1834 and the other in 1847/49, four Algerian women are inside an apartment in Algiers. Where many Western European painters painted foreign women with an eye to exoticism, eroticism, and Orientalism, Delacroix’s earlier painting is especially notable for doing none of these things. The women are clothed, seated, and hostile to the viewer’s gaze. But they are beautiful, exquisitely so.

Femmes d’Algers dans leur appartement, 1834. Image from Wikipedia.

While Picasso seemed to only cite the above 1834 painting as the inspiration for his series of women in Algeria, his paintings echo more of the tone of the 1847/49 painting. Delacroix had painted the same setting, the same women, but this time with a 15 year patina of nostalgia and Western harems that renders the scene inviting, warm, and erotic. Similarly, Picasso’s women are not clothed, but one gazes out at the viewer with a smile, inviting us in. They were rendered in Picasso’s signature Cubist style though, so beauty has mostly flown the coop, though the one obvious face does seem beautiful in many ways.

Femmes d’Algers dans leur appartement, 1849. Image from Wikipedia.

Picasso’s Les femmes d’Algers, 1955

Lichtenstein’s Femme, then, borrows Picasso’s Cubist rendering but reinserts Delacroix’s 1834 hostility. This single gargantuan woman, bigger in scale than the group of women in Delacroix’s works, stares down at the viewer with her body unclothed yet also impossible to discern and find beauty in. Her hands sharpen into claws. But it’s her face, turned into the flat white circle and beak of an owl that threatens most stridently. Unlike the harems that Delacroix’s later painting and all of Picasso’s paintings imply, this woman is not inviting us in, she is not meant to be touched. She is monstrously untouchable.

Femme d’Alger, 1963. Image from The Broad.

The first time I saw it, I found it empowering—a reclaiming of her autonomy from a century of the male gaze invading her apartment. And I suppose it can still be read that way; that’s the nice thing about art, it’s subjective. But after reading Steiner, I wonder how much of this woman’s untouchability is a result of a hatred of beautiful women. Steiner talks a lot about men seeing beautiful women, being enthralled, and then realizing that their beauty is not for them. The response from men is often violence, as when Frankenstein’s creature frames Justine for murder when he realizes that her beauty is not for him. Lichtenstien’s Femme d’Alger seems to anticipate that violence, and meet it with a threat herself, just as his other women seem to be waiting to ask us why we’ve put them in this predicament in the first place.

Currently Reading

In addition to Venus in Exile, I picked up The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois today. It was a deliberate choice, to begin reading it on the Fourth. A slightly different way of celebrating. Its a short book, only about 90 pages, but so far it already has the overwhelming sublime power that I felt reading Between The World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Told a hundred years earlier, the essays in this book exam how racism veils every moment of the lives of Black people in America at the turn of the last century. As part of the first generation of Black Americans born free, and the first Black person to get a doctorate from Harvard, DuBois’ book is an invaluable perspective on where the US is coming from, and where we’re still heading.

This is the free edition of Collected Rejections. If you liked it, click that little heart at the bottom to tell me so! Go ahead share it with your friends too.

Was this email forwarded to you? Cool! Subscribe for more right here: