035: How Doing Ecstasy Saved My Life

Hey friends,

I’m still feeling the same strange and spacey energy that I was two weeks ago. A lot of you responded to that last essay sharing that you were sort of feeling the same—caught between two places, two lives, two selves. I’ve been wondering the last few days if we’re all just trying to figure out who we are after covid and how we move on. I don’t have an answer, but if you’re still feeling that way (or just starting to feel that way) just know that you’re not alone in it.

Right now I’m working with Sarah von Bargen to figure out what comes next for me writing and business-wise. So you might see this newsletter evolving (more!) pretty soon! That’s also why this essay is a day late.

Today I’m telling a story I’ve wanted to write for a while, but always been a bit nervous about admitting to in writing. But, more and more people are starting to recognize the positive pharmacological effects of MDMA, so I wanted to add my story to the pile. Doing ecstasy saved my life. Here’s how:

It was October of 2015. I was in the last months of a harrowing job, but I didn't know it yet. I had recently spent time in the hospital, my best friend and I had lost touch. I was suicidally depressed, and I didn't really see the point in continuing to try to get better. I was at the end of my rope, but I wasn't ready to let go yet.

The hows and whys of what happened next are lost to me now. I don't remember whose idea it was to do ecstasy and go to a rave on Halloween. I remember I agreed because I didn't have a good reason not to, because a guy I liked was going, and because I had developed such a debilitating fear of being touched even lightly by strangers that I knew I couldn't get through something as crowded as a rave while sober.

When the night came, we dressed up, arrived at a warehouse/concert venue somewhere in Dallas, got a drink, and then my friend showed up with the ecstasy in his pocket. For a while I stood around uneasily, waiting for it to kick in.

I’d been around people on ecstasy in the past. They were always overly friendly, super touchy, very interested light shows, and sort of generally looked like they were having fun. While my friends clearly started to experience this, my reaction lagged behind. All I ever felt that night was normal—which is to say, the depression finally let go for a little while. I knew it was working when the crowd didn’t seem intolerable anymore, when I could stop dodging other partiers long enough to actually dance and enjoy myself.

My friends stayed at my apartment that night, finally falling asleep on couches and in sleeping bags around 7 am. I laid in bed and stared at the ceiling long past sunrise, worried about what came next. I’d been warned about the dangerous crashes, about the terrible depression that would encroach once the drug worked itself out of my system. Could my depression be worse than before? I wondered. I wouldn’t survive the week if it was.

Here’s the science: MDMA works by stimulating the brain’s serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine centers. These neurotransmitters are created in the brain using proteins. They carry messages throughout the brain and the body. Not having enough of them, especially serotonin, is linked to depression and other mood disorders. The cause of missing serotonin could be a lack of proteins needed to make it, could be that the brain just isn’t making enough, or that the receptor sites aren’t able to receive the serotonin correctly—Big Science actually isn’t sure which is the main problem. SSRI medications, which treat a range of mood disorders, add a slow drip of serotonin to the brain, which is why they can take a long time to make an impact.

MDMA is sort of like an ice bucket challenge, but with serotonin. You dump in a bunch at once, shiver, then dry off thoroughly.

I’ve heard what ecstasy actually does described as sort of forcing the brain to give up all of the serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine it has stored up, like a bully taking your lunch money. Then it helps receptor cells receive all those extra neurotransmitters, making you feel better than ever. But because it takes time for your brain to make more of each, MDMA makes users crash into terrible sadness or depression for the next few days because they’re completely out of serotonin. You can’t eat lunch without lunch money, right?

So that’s where I was laying in bed that night—the drug was already wearing off, and I knew the crash came next. I knew it could be dangerous. But for one night, for the first time in years, I’d felt happy. I fell asleep knowing that however I felt the next day, the risk had been worth it.

But then… I didn’t experience that crash. I felt fine the next day, and the day after that.

Better yet, in the weeks following the depression never regained the same grip on me that it had before I took ecstasy.

From my perspective, there was no good reason for me to feel any better. My nightmare job was still a nightmare. I was still on bad terms with people I loved. My physical health was questionable at best. So what gave?

I started finally doing research about MDMA done by professional researchers instead of just asking my friends (ha). The first thing I found was a 1990 summary of research done in Switzerland on the positive impacts of psychedelics. That summary is literally one month younger than me. Looking for newer things, I found a 2010 episode of Stuff You Should Know that covered how psychedelics have been used to treat mental illness, as well as how they became illegal in the USA in the first place. (Give that one a listen because that story is both hilarious and frustrating.)

They were saying the same thing—MDMA has been well-documented to improve pro-social behaviors and make people feel immediately happier through very clear, decently understood, chemical reactions. In 2015, Scientific American published an article saying,

MDMA’s effects on serotonin, a key player in all hallucinogenic drugs, accounts for its users’ increased sensitivity to music and appreciation of light shows, reflecting the drug’s popularity at raves. Its stimulation of norepinephrine and dopamine release may explain the euphoria and increased energy users experience, and increased cortisol levels are implicated in decreasing fatigue. The prosocial effects—the desire to socialize and bond with others— have been linked, though controversially, to MDMA’s effects on brain concentrations of the hormone oxytocin.

Long-term effects, however, haven’t been studied in the US because in 1985 the DEA ruled MDMA a drug with “high abuse potential and no approved medical use” (Scientific American) after one highly flawed and ridiculous study that should have never been paid attention to (SYSK). (That story is funny in a fatalistic wtf-is-the-US-government-even-doing sort of way, and I think Josh & Chuck just tell it better, so go listen to that SYSK episode.)

I found these studies interesting, but none explained why I felt significantly better for so much longer after.

To be clear, my depression wasn’t 100% gone. But the suicidal impulses were. And I was able to more clearly reflect on the trauma I had experienced and deal with it better, post-MDMA. That allowed me to use talk therapy to heal better.

I talked about the experience a year later with my psychiatrist in France. (I never told my therapist in Texas that I’d done it, I’m not sure why.) She passed on a theory and analogy she’d heard professionally—computers mimic human brains in lots of ways, including the way they sometimes get out of wack. Everyone’s faced this problem: A program freezes for some reason, or the whole computer is acting weird, and the first piece of advice a tech person will give you is, “turn it off then turn it back on.” Does it always work? No. But it often does. MDMA, she thought, might have had the effect of turning off the serotonin-creating part of my brain, then turning it back on. It gave that “program” a chance to “reboot.” It worked, and it kept working.

She thought that if my brain had been extremely impaired in creating serotonin and dopamine, that would also explain why my reaction to the MDMA was so mild. MDMA forced my brain to give up its lunch money, but the poor thing only had 50 cents in its pockets. While my friends who took ecstasy from the same batch I did were clearly high and loving the light show and each other (ahem), I got to not-hate being in a crowd. When they were all crashing the next day, my poor brain was already used to not having any serotonin, so I felt basically the same as I had for years. But afterward, my brain started to get better at creating all those feel good neurotransmitters. The depression faded.

In fact, after MDMA, I got significantly better. For years now, I’d say that the times I have felt depressed were shorter, less intense, and less dangerous. I still feel better able to cope with those periods too. Part of that was talk therapy, but I’d been in therapy for six years before trying MDMA as well, with much slower progress.

There’s a vogue right now for studying MDMA, especially how it helps people with PTSD heal. Scientists are realizing that in addition to boosting feel-good chemicals, MDMA suppresses the amygdala, helping people confront negative memories better without the strong emotional component. They process trauma with less fear, less anger, and more understanding. University of Chicago professor Harriet de Wit is one of the leading researchers in this field, and she did a really great interview on Big Brains about her work. She’s seen what I experienced: the healing effects of MDMA weren’t immediate, but got stronger the more users reprocessed within a therapeutic setting.

(de Wit also talks about microdosing in that interview, which is much less scientifically understood. She proposes that the positive effects are linked more to confirmation bias, placebo effect, and other psychological principles.)

Am I saying that if you’re depressed you should try ecstasy and go to a rave? Well, certainly not without supervision by a doctor and/or chemist—there’s no way for you to know what street ecstasy is mixed with. That rave was the biggest gamble I ever took—I got lucky that it had the overwhelming positive impact that it did.

Three years after I went to that rave, Michael Pollan published How To Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. Start there, if you’re interested.

I haven’t done MDMA since. I’ve never felt particularly interested in most drugs, honestly. But this experience saved my life, and continues saving me. I’m excited to see where the science takes us next.

Things I Read and Loved This Month

Hot Divorcée Summer, by Lyz Lenz

Stages of Grief: What The Pandemic Has Done to the Arts, by William Deresiewicz

What Instagram Really Learned from Hiding Like Counts, by Casey Newton

A Star Is Born: The History of the Asterisk, by Claire Cock-Starkey

Towards A Unified Theory of Peloton, by Anne Helen Petersen

The Unexpected Beauty, by Cheryl Strayed

Champagne from Champagne, Mokha from Mokha, by Marianne Dhenin

The Women Who Want to Be Priests, by Margaret Talbot

Currently Reading

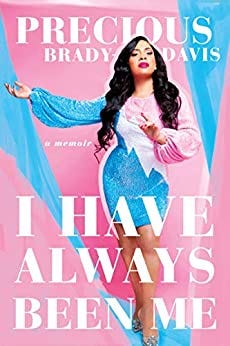

This book is as much as memoir as it is a love story. In I Have Always Been Me, trans right activist Precious Brady-Davis walks us through her childhood of neglect, instability, and religious fanaticism, through to her own powerful discoveries of love and self-love. It’s strange—I’m very aware that I’m being told a story by someone, which I normally hate. However, her voice is so fun and engaging that I don’t mind. I could listen to Precious Brady-Davis talk all day.

This is the free edition of Collected Rejections. If you liked it, click that little heart at the bottom to tell me so! Go ahead share it with your friends too.

Was this email forwarded to you? Cool! Subscribe for more right here: