007: What We Read & Who We Care About

When I first started doing the 00# numbering system for this, I planned that this email, number 007, would be about, well, 007. I love James Bond, even though most feminists tell me that I shouldn’t. Bond himself is a womanizer and probably a clinical sociopath, and the movies range from mildly to wildly misogynistic. I know this. And yet, he’s a favorite. A deeply problematic fave, to be sure, and I’m always first in line to criticize the Bond series. But the world of espionage is inherently a problematic space. It exists outside of civilian law, and different rules apply. Plus, it’s fiction.

Of course, that’s the logic people use to excuse all kinds of bad behavior/exclusionary fiction. And that can be dangerous because a lot of studies show that what we read (and probably watch, though I haven’t seen as many studies on this) directly impacts who we care about.

Scientists call it ‘emotional transportation.’ Basically, when we read fiction we take on the emotions of the protagonist. The more we like the story, the more we’re emotionally transported, and the bigger impact it has on our empathetic responses in our real lives. You’ve felt this if you’ve ever put down a story and felt like you missed the characters, or like you had ‘readjust’ to the real world. That’s emotional transportation.

People who are more emotionally transported tend to engage in more prosocial behaviors. Prosocial behavior is anything that works toward the common good. Stopping at a red light is a type of prosocial behavior. Picking up litter, volunteering, wearing a mask (ahem)—these are all prosocial behaviors. They happen more when we understand how our behavior impacts other people, which can be achieved by being ‘transported’ into someone else’s emotional world.

Interestingly, reading non-fiction does not often evoke the same response in our minds. I mean, I’m betting it depends on the type of non-fiction, though I didn’t find a study supporting this. Between The World And Me, a father’s letter to his young son about the impact of racism on his life, probably achieves emotional transportation in a way that A World History of Art, being a textbook, simply doesn’t. At least, one of those made me cry and the other didn’t (you get one guess for which is which). Nevertheless, according to at least one study, non-fiction can actually increase feelings of loneliness and decrease prosocial behaviors. (I wish I knew what non-fiction they were having participants read in these studies.)

Anyway, so people who are emotionally transported by their reading were up to three times more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors after reading. Reading just one short story can impact people for up to a week. It follows that reading a lot of fiction repeatedly could shape people’s behavior for longer periods of time. And therefore, being emotionally transported by fiction while young and impressionable could create permanent impact. Which is exactly what scientists studied by having kids read Harry Potter. (All the studies I’ve mentioned before now have been college students at the youngest!) Despite Rowling’s own intolerant views toward LGBTQIA+ minorities, Harry himself is extremely kind toward every minority group he encounters, and he rejects ideas like eugenics and fascism, which are inherently exclusionary and hostile toward minority groups. So when readers are emotionally transported into Harry’s head and his world, they learn that same empathy and tolerance that he models. Kids that grew up with Harry are statistically more empathetic than their peers that didn’t read the books.

However, reading fiction only works if the reader isn’t already consciously hostile to the group they’re reading about. So if someone hates queer people, reading Little & Lion isn’t going to suddenly make them an LGBTQIA+ ally. There are limits. It also only increases empathy for the characters you read about. Emotional transportation doesn’t make readers more empathetic in general.

Which is why what’s on your bookshelf and what you read matters. Knowing that, I decided to do an inventory of my bookshelves last week, both ebook and physical. I looked at every book I own and created a spreadsheet noting first genre, then the gender, sexuality, and race of each protagonist and author. I apparently own 304 books (what the fuck), so this process took days. (In fact, I wanted to write this last Tuesday but it took me until last Thursday to fully get everything entered and analyzed, then several more days just to graph it all.)

I was really dismayed by the results.

Until I did this, I thought I was pretty good about reading widely about diverse characters from diverse authors. I have consciously sought out books by Black authors in the past, and deliberately bought and read queer romances, but it turns out that, well… Let’s dive into it.

A full 84.5% of my bookshelves are books written by White authors. Only a pathetic 5.4% of the books I own were written by Black authors. The other 10% is split between Asian (2.7%), Indian (1.4%), people of mixed race/ethnicities (1%), Latinx (.7%), Pashtun (.3%; it’s just the book I Am Malala), Unknown (2.7%; mostly books with anonymous authors), or Other (.3%, an anthology with multiple authors).

How does that compare to general US population? 60% of the US self-identifies as White, 13% as Black, 18% as Latinx, 1.3% as Indigenous American. So, despite being primarily bought from US stores, and US publishers, my bookshelves do not represent the real ethnic and racial backgrounds of the US.

Now, if you thought that the race of protagonists would mirror the authors, that’s actually not necessarily the case.

75.9% of the books I own have a clearly White protagonist. (85% of authors are White though… We’ll come back to this.) 6.5% feature a Black protagonist, 2% have an Asian protagonist, and the rest are Arab, Indian, Mixed race/ethnicity, Latinx, or a mythological creature that doesn’t fit into one of our racial categories.

(A caveat: I only noted books that have a clear protagonist. So most of the non-fiction I own is not included in this pie chart, except biographies. The ‘Other’ category is for mostly short story collections that have numerous protagonists and therefore were too hard to categorize.)

Basically, White people aren’t exclusively writing about White people. But, at least in the books I own, authors of other racial or ethnic backgrounds aren’t crossing that racial/ethnic boundary the same way. In the books I own (and that is a big factor to take note of), Black authors are writing about Black people, Latinx authors are writing about Latinx people, etc. Indian authors aren’t writing about Black characters, though. In only one book (on my shelves) did an author from a minority group leave a character’s race/ethnicity ambiguous: Celeste Ng in Little Fires Everywhere, because she wasn’t sure she could do justice to the Black experience, so she left only breadcrumbs and never made race explicit.

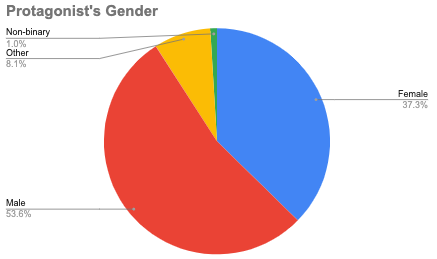

A similar trend follows for gender and sexuality as well.

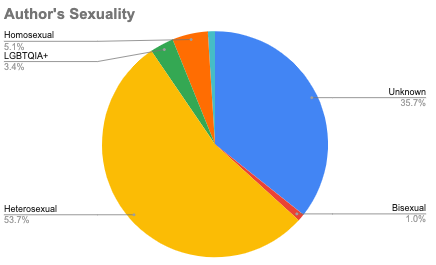

Here’s the thing: Numbers don’t lie. However, data can obscure. Sexuality is an especially unreliable metric here, and I want to make that clear. Prior to 1850, ideas of sexuality simply didn’t exist the same way that we consider them. Our most common modern categories of sexuality (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual) weren’t widely known (let alone accepted) until the early 1900s, not to mention the rest of the spectrum of sexuality as we understand it. So that’s worth noting, especially because a lot of my books predate modern categories of sexuality. (This is what I get for studying the Victorian Era [1837-1901] for my MA.) For those authors and protagonists, I guessed how they might identify as best as I could, but anytime there was any doubt in my head I marked an author’s sexuality as ‘Unknown.’ Which is why that category makes up a full 35% of my books.

So, what it looks like is that heterosexual authors aren’t necessarily writing about heterosexual characters. Like race, they cross the boundaries of writing about people different from themselves pretty frequently. Male and female authors also feel free to write about someone with a different gender identity than them. (Harry Potter and Andy Weir’s Artemis are good examples here.) Basically, people in majority groups who hold the most power—White, male, heterosexual—feel okay writing about someone from minority groups. But people in minority groups aren’t writing about people from majority groups.

In fact, only a measly TEN PERCENT of my books could be considered Own Voices books. An Own Voices story is any story where a protagonist from a population group is written by an author from that population group. So, if your character is a heterosexual Arab female (Artemis, by Andy Weir), then the author would have to be a heterosexual Arab female to be an Own Voices story (Andy Weir is not).

For the record, I was pretty conservative about categorizing Own Voices stories. Philippa Gregory, for instance, is a white woman writing about white women, but her characters all lived 500 years ago (she writes great historical fiction about the Tudor Era). Since I highly doubt that Gregory’s life today reflects the same lived experience as Anne Boleyn’s, I don’t consider The Other Boleyn Girl an Own Voices story.

For the record, this isn’t necessarily bad. Women of the Tudor Era weren’t as educated and didn’t have the leisure time to write novels about their lives. Most of what we know about their lives was written by contemporary rich male historians who had agendas (glorifying the Tudor Era). So with the right amount of research, Gregory’s books can still be an important resource for understanding the lives of women back then. And she’s generally pretty lauded for treating historical characters with sensitivity and accuracy.

It’s when you get biased authors who didn’t treat their characters with compassion, like Arthur Conan Doyle writing really racist depictions of Asian immigrants in London in that 1880s (which he did from time to time), that crossing racial/ethnic/gender/sexuality lines becomes a problem. Because if reading engenders empathy in us, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story only engenders empathy for the white upper class people like Holmes that he treats with care. And, worse, since the stories encourage us to empathize with Holmes, we’re learning to empathize with Holmes’ racial biases too. Conan Doyle’s stories could, theoretically, make us more racist by teaching us to empathize only with Holmes and Watson and no one else.

So, what does this mean? What’s the point here? Why did I go through all this?

Well, if reading books dictates who we empathize with—and even adults are subject to this—then my bookshelves are teaching me to empathize with primarily straight white dudes. And I bet your bookshelves are too.

Because the issue is bigger than just my bookshelves. It’s what publishers think is worth printing, and what bookstores both to sell. Male leads in fiction sell 10 million more books on average than female leads. That analysis literally does not even bother to include trans characters or non-binary characters. People of color only accounted for 22% of protagonists in children’s fiction in 2016. This is a whole lot less than the roughly 40% of the US population that are people of color. Even worse, in 2017 and 2018 combined, only 18 young adult books were written with LGBTQ characters of color. Eighteen. Total. In two (very recent) years.

Last year, when I wanted to start Diogenes Club Books, I wanted to only sell books by Black authors during the month of February for Black History Month. I wanted to sell only books either by LGBTQIA+ authors or featuring LGBTQIA+ characters during June for Pride. Obviously, my bookstore/coffee shop plans didn’t pan out (and honestly, thank God, considering the economy right now). But I wish someone would do this. I wish publishers would dedicate a year to only publishing books by minority authors. I wish that publishing wasn’t so systemically conservative and racist and sexist and homophobic that these authors got published, their books got equal shares of marketing budgets, and they were featured in bookstores at the same rate. I wish people (I) didn’t have to seek out diverse books and ask themselves, “Hey, have I ever read a book by a queer author of color?”

What we read dictates who we care about. And who we care about dictates who we befriend, who we root for, who we give basic civil liberties to.

So, you know... Maybe if you want to make the world a better place—if you want to dismantle white supremacy, if you want to be anti-racist—that starts with reading more diverse fiction. This summer, read a book by LGBTQIA+ authors, by Black authors, by and about people from outside your general population group. Gift these stories to your friends, to your kids. Recommend them. Post them on Instagram.

Because who we read about is who we care about.

As always, thank you for reading. If you want to respond just hit reply. Your message will get to me (and only me). If you like this and think your friends might too, feel free to forward it on.

I keep these newsletters free by not worrying too much about typos and flow. But if you want to you can tip me, as a treat.

I write things! Most recently I wrote about all those virtual tip jars you’re seeing on Instagram for Barista Magazine. Check it out here.

If you received this email from a friend and you liked it, you can subscribe to this irregularly written series over here.

Stay healthy, friends!

xx,

Valorie